We are living in unprecedented times where our levels of stress are at an all-time high. We may be stressed about the fragility of our health and the health of our loved ones, we may be stressed about our work and finances. Some of us have lost our jobs and others are adapting to a totally new way of working either remotely or in an environment with PPE and ’social distancing’. Even prior to COVID19 we were living in a world where stress was the predominant constant in our lives. The article below explores what stress is and how it impacts our brain health.

From the moment we open our eyes in the morning to the second we go to sleep at night, for many of us, our systems are in a heightened state of stress. The effects of stress are well documented in relation to a myriad of health conditions for example cardiovascular disease, obesity, and migraine. However, the effects of stress on our brain health, short term and under chronic conditions has had little attention.

WHAT IS STRESS?

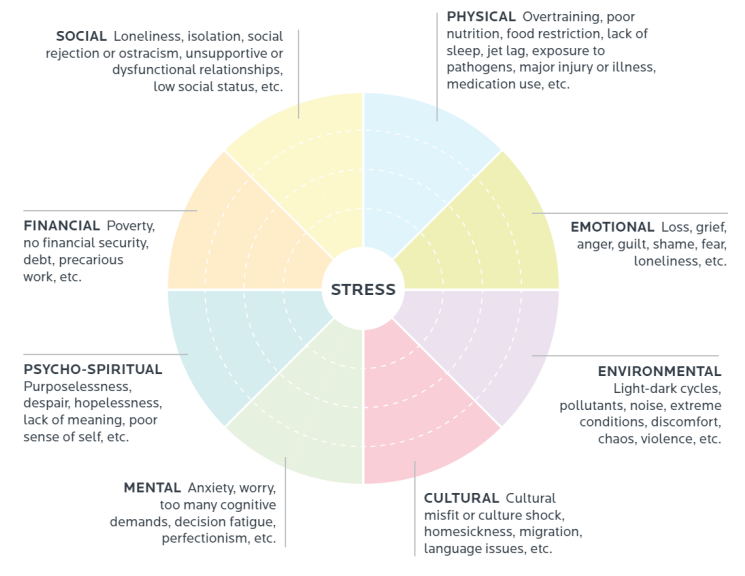

We all generate an image in our minds when we think of stress – work, relationships, financial worries, house moves, divorce, bereavement, and even social gatherings for some. There are however, other scenarios which our bodies ‘perceive’ as stress which are less obvious – pain, over-exercise, nutrient deficiencies (poor diet and dehydration), blood sugar imbalances, imbalanced gut flora, anti-nutrients (caffeine, drugs and alcohol), food intolerances, food additives, toxins, infections, pain, as well as thoughts, beliefs and perceptions. All those things, we lived with day to day, long before the added strain of COVID19. Any of them can be perceived as stress by our system and the effects vary hour to hour, day to day, person to person, as does our ability to cope and respond. The stressor can be short lived and the effect short-lived, or it can be chronic where the impact can be longer term and significantly more damaging.

What happens when we are exposed to a stressor?

Stress begins in the brain. Our senses, touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste, all gather information and send it to the brain. Whether it be pain, or a job interview the body interprets and processes the threat in an area of the brain called the amygdala. From there the amygdala switches on two other systems – the hormone system and branch of the nervous system called the sympathetic nervous system.

The hormonal response to stress works through the HPA or hypothalamic pituitary adrenal access. Stress is sensed first in the brain. The hypothalamus responds by releasing CRF (corticotrophin releasing factor) which stimulates the pituitary to release ACTH (adrenocorticotrophic hormone). ACTH acts on the adrenal glands stimulating the adrenal cortex to release cortisol. The adrenals sit on top of your kidneys and are the chief glands responsible for dealing with stress and in response to any stress, they respond by secreting certain hormones like cortisol and adrenaline (epinephrine and norepinephrine). If you can visualise it, you step out in front of a bus. Adrenaline kicks in and makes your heart rate race and it is cortisol that then keeps the heart rate high.

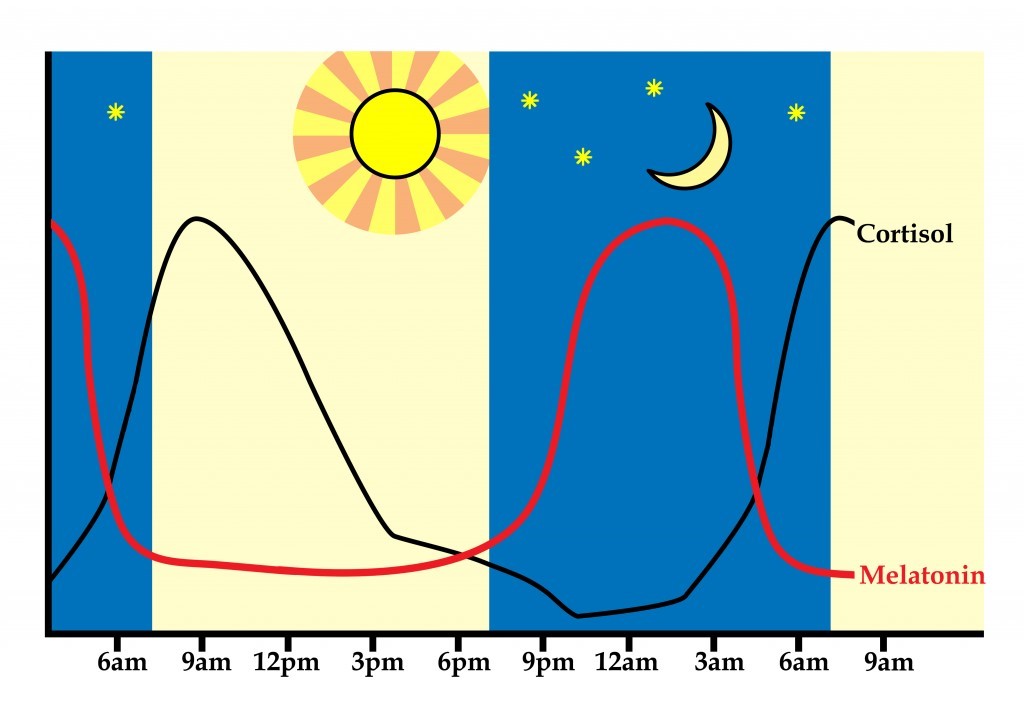

Levels of the stress hormone cortisol naturally follow a circadian rhythm, rising rapidly after waking, falling during the day, rising in late afternoon before dropping to lowest levels in the middle of the night. They move in direct opposition to the hormone melatonin which you may be familiar with in respect to its effect on promoting sleep.

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system results in physiological responses

- Breathing becoming faster and shallower

- Increased heart rate

- Increased cholesterol

- Inhibited digestion

- Inhibited immune function

- Increased muscle tension

- Increased release of cortisol, adrenaline, and other stress hormones

Increased production of cortisol further promotes these physiological responses via a number of mechanisms including increasing the availability of glucose in order to ready the body for action, in other words, to facilitate the ‘fight or flight’ response. As well as increasing the body’s readiness for action, cortisol suppresses processes that are not needed immediately e.g. the highly demanding immune system.

Therefore, stress can increase susceptibility to coughs / colds and other infections. Once the challenge has passed, the human body should release and relax. Of course, in today’s environment, there is often no recovery, just ongoing stimulation of the stress response.

A positive side to stress?

There is a tendency to believe that all stress is negative. However, before we talk about the negative effects of stress on the brain, we need to remember that our stress response is a normal physiological response.

Stress can be motivating, for example when studying for exams.

It is a cognitive enhancer. It helps our brain to focus. Stress developed to help us to react to potentially dangerous situations in the wild – and this might mean for instance trying to escape from a predator. Stress also been shown in some studies to help increase memory and recall – so a little stress while revising for an exam or a presentation can help you to remember what it is you’ve read on the big night. This is supposed to be a result of slightly higher levels of cortisone.

It is physically enhancing and can improve your physical strength and endurance. This may have once helped us to run for longer when being chased, but today it might help us in a physical confrontation, or during a sporting event. A bit of stress for an athlete then is a beneficial thing. Adrenaline can also help to fight tiredness and fatigue

However, there are 2 very important things to note when reviewing this information. Firstly, all of these positives to stress are associated with exposure to a short-term stressor and all stress responses are dependent upon how one perceives the stressor. Kelly McGonigal, a health psychologist, in her book ‘The Upside to Stress’ discusses how our belief about stress is a crucial factor in how we are affected by it. A 1998 study changed her perspective on stress and led to further exploration. In 1998, 30,000 adults in the US were asked how much stress they had experienced in the past year and whether they believed stress was harmful to their health. Eight years later the researchers looked to see how many of the 30,000 had died.

The results showed high levels of stress increased risk of dying by 43%, but this was only related to people who also thought that stress was harming their health. The study concluded that it was not stress alone that was killing people but a combination of stress and the belief that stress was harmful. A different message from what we are used to but an interesting one.

The negative effects of stress on the brain

Stress can be directly linked to common brain health issues such as anxiety, depression, low mood, brain fog and even tiredness. An underappreciated fact is that the raw materials for the synthesis of many neurotransmitters are nutrients – amino acids, vitamins, minerals and other natural biochemicals that we obtain from food (and supplements). Acute stress can often mean we make bad food choices, eat under time pressure, do not chew correctly and sometimes miss meals. Long term chronic stress inhibits our ability to digest by reducing gastric and intestinal secretions, induces changes to our microbiome and can promote diarrhoea. Chronic stress can also promote unhealthy habits due to its impact on our blood sugar levels. Blood sugar irregularities can generate cravings for that chocolate bar or sugary drink. All of these can play a role in depleting your stores of essential nutrients or even hinder their absorption completely.

Stress also uses up nutrients. Any nutrients that support your heart, lungs, and muscles such as magnesium, B vitamins and vitamin C, are going to be redirected there as a priority. You also must consider that your adrenal glands will be working overtime to produce stress hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol so will be utilising plenty of vitamins to make sure this is getting done properly. To give just one example of how this might affect your mood consider serotonin. Serotonin is produced from the amino acid tryptophan, a constituent of protein, and the final reaction step requires vitamin B6. Vitamin B6 is utilized in the synthesis of the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine. This means that, when you are stressed, there is less B6 available to perform its other functions. Vitamin B6 is also essential to the formation of the feel-good neurotransmitters’ GABA, and dopamine. Without the presence of sufficient amounts of neurotransmitters neurological symptoms such as depression and anxiety can develop. With more severe deficiencies e.g. dopamine Parkinson’s-like symptoms can be evident. In the absence of neurotransmitters research shows evidence of neurite retraction and death which is the hallmark of cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease and dementia-type symptoms.

Unlike muscles, which can store excess carbohydrates, the brain needs to be constantly supplied with oxygen and energy, in order to function properly. The draining of vital nutrients such as B vitamins, Magnesium, Iron and Manganese can result in insufficient energy production within the mitochondria of neurons and a lack of oxygen rich blood flow to the neurons. Manganese also forms the core of an antioxidant superoxide dismutase enzyme, located inside the mitochondria, the intracellular organs where the Krebs cycle operates. Oxidative stress and/or energy and oxygen depletion can again result in neurite retraction.

Chronic stress may result in changes to neuronal (i.e. nerve) structure and function and also neuronal death, thus it may accelerate the process of brain degeneration that eventually leads to dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Increases in plasma cortisol levels have been reported in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and a correlation has been found between increases in 24h cortisol levels and the severity of cognitive defects in Alzheimer’s. Deficits in learning and memory have been reported in rodents after chronic stress. Chronic, i.e. long-lasting, increases in cortisol secretion have been found to:

- Induce neuronal loss in the area of the brain important for short-term memory, the hippocampus. One of the functions of the hippocampus is to inhibit over-activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) and so stress could initiate a vicious cycle of HPA over-activity and neuronal loss in the hippocampus.

- Stress suppresses neurogenesis and reduces the expression of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) – a growth factor produced in the brain, sometimes called ‘miracle-gro’ for the brain.

- Stress increases inflammation and studies in mice suggest that stress hormones may increase the production and toxicity of beta amyloid. It is also possible stress increases tau tangle formation. Both beta-amyloid and tau tangles are part of the pathology of Alzheimer’s.

- Stress can cause high blood pressure and other vascular factors that are related to both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

Stress can also have detrimental effects on brain function by:

- Increasing blood sugar. This can lead to an increase in the production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) which cause damage to cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA. High blood sugar can lead to insulin resistance and the brain may become insulin resistant years before other tissues in the body. Insulin resistance can result in brain cells being ‘starved’ of fuel because glucose cannot effectively enter cells.

- Affecting thyroid function. Stress and cortisol in particular, increases conversion of T4 to reverse T3 instead of the active thyroid hormone T3. This can result in T3 and rT3 competing for binding sites at the receptor of the target cell. This can result in symptoms of reduced thyroid function like low mood. Also, optimal thyroid function is crucial for optimal cognition as the thyroid gland sets the pace for the metabolism. Suboptimal thyroid function is common in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Affecting testosterone, progesterone and oestrogen levels and oestrogen sensitivity. All hormones in the body are produced form the same precursor – cholesterol. A phenomenon exists whereby long-term chronic stress results in high levels of cortisol being produced. The draining of the raw material, cholesterol can result in lower levels of other hormones such as progesterone, testosterone, and oestrogen. This is commonly referred to as the ‘cortisol steal’ or the ‘progesterone steal’. To further compound this in pst menopausal women, the primary source of oestrogen becomes the adrenal glands. Unfortunately, if they are occupied with pumping out cortisol, they will not be focused on oestrogen production. The role of oestrogen and progesterone in cognitive function remains controversial, but there is strong evidence for such a role. Oestrogen also binds to its receptor and activates an enzyme called (alpha secretase) that cleaves Amyloid precursor protein in such a way that it sends out a duo of subunits that are supportive of synapse building. Testosterone present in both males and females supports the survival of neurons.

- Affecting gut health – cortisol suppresses gut immunity with the consequence of increased growth of undesirable gut microbes at the expense of the beneficial gut microbes. This imbalance in gut flora can contribute to the development of leaky gut; in turn leaky gut contributes to systemic inflammation in the body and ultimately brain inflammation. LPS (lipopolysaccharide) produced by some types of undesirable gut bacteria has been found in beta-amyloid and there is a suggestion that LPS triggers the production of increased beta-amyloid.

- Affecting sleep and reducing both sleep quantity and sleep quality. Sleep is important for cell repair and regeneration and beta-amyloid clearance. Reduced sleep can impair brain function. It can also increase the hunger hormone ghrelin, making us hungrier the following day and leading to poor food choices and an increased craving for sugary and starchy foods.

Nutrition and Lifestyle intervention have an essential role to play in the management of stress and therefore in the management of all brain health concerns from something as inconvenient as forgetting your key to situations of severe cognitive decline such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Essential to regaining cognitive ability or ameliorating any mood disorder

- Intake and absorption of supportive macro and micro-nutrients both in food and supplemental form. There are a number of nutrients that are important for helping the body cope with stress – some nutrients are calming such as magnesium and pantothenic acid, others support the adrenal glands that produce the stress hormones, e.g. B vitamins, vitamin C (pantothenic acid is also used by adrenal glands). Foods that are good sources of magnesium and B vitamins include nuts and green leafy vegetables. Vitamin C – again, green leafy vegetables and fruit (but choose low sugar varieties). There are also herbs that people use to help cope with stress. For example, ashwagandha is a herb that is used in Ayurvedic medicine to support sleep and calmness. Siberian ginseng and liquorice are often used in formulas to support the adrenal glands (glands that produce the stress hormones) and are often used when stress has been going on for some time and the person has started to feel fatigued (unremitting long term stress can lead to ‘burn out’ and exhaustion). Teas – chamomile tea has calming properties and, of course, black tea contains L-theanine which increases levels of brain calming chemicals – may be why “a nice cup of tea” is often offered as comfort.

- Balancing of blood sugar – Blood sugar crashes cause the release of cortisol, which helps raise blood sugar levels again when they crash. However, if poor diet is causing blood sugar crashes through the day then levels cortisol will be elevated for long periods – contributing to increased feelings of stress. Feelings of stress can cause cravings for high sugar foods, leading to a vicious cycle. Stress can be supported by eating a diet that keeps blood sugar balanced and which provides adequate nutrients for the adrenal glands, involved in the stress response. This is a low sugar diet, high in vegetables with adequate protein and healthy fats

- Recovery and support of the adrenal glands with both nutritional and lifestyle interventions (see below)

- Balancing of the stress response – do we view stress as a negative or a positive? Can we learn to just say no?

Lifestyle interventions to support stress management

Nature

Studies have shown that watching wildlife (e.g. birds), spending time in nature, or even watching natural history programmes can reduce stress and anxiety and improve mood. So, try swapping high tension drama for David Attenborough on the television.

Breathing

Certain types of breathing can stimulate ‘the relaxation response’. For example, breathing in through your nose for approx. 7 seconds, pausing, and then breathing out slowly through your mouth for approx. 11 seconds. Try 2 or 3 breaths to start with and build-up to repeating 12 times. Repeat at least once daily. While carrying out this exercise you can try visualising a word such as ‘CALM’ or a relaxing scene.

Meditation

Meditation has become one of the most popular ways to relieve stress among people of all walks of life. This age-old practice, which can take many forms and may or may not be combined with many spiritual practices, can be used in several important ways it affects the body in exactly the opposite way to how stress does.

‘Meditation on Steroids’

Products like ‘Revitamind’ are available. They contain audio tracks available to be downloaded and transferred to your such as an iPad, iPod or smartphone. These recordings are not ‘music’ in the traditional sense but rather specially crafted ‘pulsed tones’. These pulsed tones stimulate and entrain your mind to provide substantial cognitive benefits when used regularly with headphones. Think of it like ‘neural exercise’ or ‘effortless meditation’, with a lot more benefits.

HIIT Exercise

Everyone is different and responds to exercise differently. In those who suffer from high stress or adrenal fatigue, HIIT could cause serious harm to health. However, done correctly, HIIT provides numerous health benefits and can support re-sensitising blocked receptors. To maximize its benefits, it needs to be done the right way and in moderation. Compounding an already high-stress work or general life stress with the excess stress from exercise can actually make a person sick. Adequate recovery from HIIT is vital in balancing hormones and avoiding adrenal burnout. Limit your high-intensity exercise to 2 times per week allowing adequate recovery time between session Make sure to get adequate sleep.

Happiness & gratitude journal

This relates to the fact that our thoughts, perceptions, and beliefs can trigger the stress response or equally the relaxation response. A gratitude and happiness journal is a notebook that you can keep next to your bed and complete daily (only takes a couple of minutes). The key to this exercise is finding some positives from the day. It is particularly beneficial to do at bedtime as it will give a positive feeling to the end of the day as you get ready for sleep; reflecting and ‘framing’ your day in a positive way (even the worst days can be ‘reframed’).

So, each night find and write down at least 3 positives from the day, they can be small e.g. it was a sunny day. This technique has been shown to increase happiness (and by association reduce stress levels) within 7 days!

Emotion

Our emotional response to stress is important. Sometimes easier said than done but try taking a “whatever” approach to stressful situations. Shrug and breathe out deeply as you say this. It works!

Eat dark chocolate

Dark chocolate (70% or 85% cocoa) can have a positive impact on cortisol levels. A Swiss study found that “the daily consumption of dark chocolate resulted in a significant modification of the metabolism of healthy and free living human volunteers with potential long-term consequences on human health within only 2 weeks treatment,” the researchers wrote, “this was observable through the reduction of levels of stress-associated hormones and normalisation of the systemic stress metabolic signatures.”

References

- Krantz, D.S., Whittaker, K.S. & Sheps, D.S. (2011). “Psychosocial risk factors for coronary artery disease: Pathophysiologic mechanisms.” In Heart and Mind: Evolution of Cardiac Psychology Washington, DC: APA.

- How stress affects your health. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/stress.aspx. Accessed Feb. 12, 2016.

- Elizabeth D Kirby et al (2013)Acute stress enhances adult rat hippocampal neurogenesis and activation of newborn neurons via secreted astrocytic FGF2 https://news.berkeley.edu/2013/04/16/researchers-find-out-why-some-stress-is-good-for-you/

- Stress and your health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.womenshealth.gov/mental-health/good-mental-health/stress-and-your-health. Accessed Feb. 12, 2016.

- Anusha Jayaraman, Daniella Lent-Schochet, Christian J Pike(2014) Diet-induced Obesity and Low Testosterone Increase Neuroinflammation and Impair Neural Function https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25224590/

- McGonigal K (2015) – The Upside to Stress. Vermilion

- The End of Alzheimer’s Dr Dale Bredesen. Vermilion

- Anderson D C (2008) – Assessment and nutraceutical management of stress-induced adrenal dysfunction. Integrative Medicine, 7, http://www.imjournal.com/resources/web_pdfs/popular/1008_anderson.pdf

- Dong H & Csernansky J G (2009) – Effects of Stress and Stress Hormones on Amyloid-β Protein and Plaque Deposition, J Alzheimers Dis, 18, 2, 459-469 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2905685/

- Epel E et al (2004) – Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stressProc Natl Acad Sci, 101(49):173125 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15574496

- Ishida R, Okada M – (2006) – Effects of a firm purpose in life on anxiety and sympathetic nervous activity caused by emotional stress, Stress & Health, 22, 4, 275-281 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smi.1095/abstract

- Johansson L et al (2010)– Midlife psychological stress and dementia: a 35-year longitudinal population study Brain, 133, 2217-2224 http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/content/133/8/2217 Martin F P J et al (2009) – Metabolic Effects of Dark Chocolate Consumption on Energy, Gut Microbiota, and Stress-Related Metabolism in Free-Living Subjects. Journal of Proteome Research, 8, 12, 5568-5579

Last updated on 7th November 2023 by cytoffice

Brilliant!

Excellent, comprehensive and readable article.

What a thorough and interesting article. Thought provoking and lots of information- thank you so much. The body is such a fascinating and clever thing. It always helps me to understand how something works, so I can understand how to help cure it! Thank you so much.

Hi there

Just read all your information about brain health.

How do I go about this workshop? Looks very interesting for myself.

I suffer aniexty and stress levels are high.

I have your tablets but would be guided what’s best for myself .

But also very interested in the extra information stated

Hi – please can you email jo@cytoplan.co.uk and she will give you a link to the programmes we are presently running on Brain Health. If you want help with your own problems please compete a health questionnaire, downloadable from our website under the tab Nutrition Advice and return to us as directed we can help you.

Thanks,

Amanda

Great article, interesting and informative, thank you