We know that antibiotics have a place in modern medicine, however, their overprescription and overuse is a long-standing problem that has created the issue of global antibiotic resistance, which has implications for both the health of the microbiome and the health of the host.1,2

Our expert nutritional therapist, Annie, looks at what approaches can help to mitigate the effects of antibiotics on the gut microbiome.

What is the gut microbiome?

The microbiome is made up of various micro-organisms and includes a range of bacteria, protozoa, fungi and viruses, that in a healthy digestive tract, all live together in homeostasis.

The microbes that reside in the gut play a fundamental role in our health as they are involved in multiple body systems including the immune system, cognition, energy homeostasis, inflammation, weight management and digestion.1,3

This is supported by research that has found correlations between certain health conditions and alterations in the gut microbiome, for example, those with type 2 diabetes exhibit poor microbial compositions with lower levels of desirable and butyrate-producing bacteria such as Akkermansia and Bifidobacterium and higher presence of a certain genera of bacteria such as Ruminococcus and Fusobacterium.4

While the microbiome should always be looked at in the context of the individual, studies like these can show a link between health conditions and their potential microbiome alterations.

Antibiotics and the gut microbiome

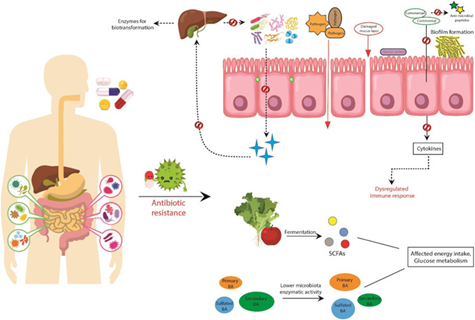

Any disruptions in this ecosystem, whether it be an overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria or low levels of the beneficial species can be detrimental to overall health. Any changes in the microbial community, as a result of taking antibiotics for example, can alter the functionality of the microbiota and affect the metabolites they produce.1

It is well-known that broad-spectrum antibiotics reduce microbiota diversity, which can predispose individuals to the overgrowth of pathogenic or undesirable bacteria, further disrupting the ecosystem.

Research has found that just a single course of antibiotics can alter bacterial diversity and produce subsequent health complications.

Antibiotics are non-selective, meaning that alongside killing off targeted bacteria, they also have a negative effect on the health-promoting microbes, causing a rapid decrease in diversity and richness in strains such as Bacteroidetes, which can take months to years to rebalance.1

In one large cohort study, the administration of antibiotics was shown to induce long-term alterations to the composition of the microbiota of children. Findings revealed a reduction of Actinobacteria (mainly Bifidobacteria), Firmicutes (mainly Lactobacilli) and total bacterial diversity, as well as an increase in the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria.5

However, it is worth noting that the authors highlighted that other types of antibiotics had less of an effect on microbiome diversity; and this seems to be very dependent on both the individual, their microbiome and the type of antibiotic used.6,7

One of the ways that antibiotics disturb the gut is by damaging the gastrointestinal (GI) epithelium, which may be in part a result of disruption to the microbiome.

Research conducted with rats uncovered that antibiotics reduced the protective thickness of the colonic mucus layer, which subsequently increased the risk of pathogen invasion and intestinal inflammation.1

Many antibiotics are also associated with a decrease in the production of butyrate or butyrate-producing bacteria, which is a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) utilised by the intestinal cells (i.e. enterocytes that line the GI tract) for fuel and to aid repair and rejuvenation.5,6

It has been demonstrated that bacterial translocation, which is the passage of bacteria through the gut lining and into the circulation, increases following a single dose of antibiotics, which is another way that this is associated with increased systemic inflammation.

This suggests an increase in gut permeability (i.e. leaky gut). These findings suggest that bacterial translocation as a result of alterations in the intestinal microflora may provide a link between increasing antibiotic use and the increased incidence of inflammatory disorders.7

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) and digestive dysfunction are common adverse effects of systemic antibiotic treatment that can last up to 2 months post-treatment. The symptoms range from mild to severe diarrhoea, the latter being particularly apparent where post-antibiotic infections with Clostridium difficile occur.1,8

Certain strains such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Saccharomyces boulardii have shown to be additionally protective against AAD.9

How do you support the microbiome after antibiotics?

Supporting the microbiome, before, during and after antibiotics is important to prepare, support and promote the healing of the gastrointestinal tract and reduce the negative effects on the microbiome.

Research suggests that the intake of certain foods containing fibre, probiotics and prebiotics, alongside probiotic supplements can modulate the gut environment and have protective and health-promoting effects.

A diverse intake of dietary fibre, whole grains and plant foods has been found to enhance the diversity and health of the gut microbiome and support overall health.

However, the standard Western diet is often low in fibre, fruits and vegetables, which can reduce gut diversity and increase the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes.1

Prebiotics

Certain fibres and prebiotics from food are metabolised by the microbes in the gut, from this, they produce health-promoting SCFAs , which include acetate, propionate and butyrate.

One of the best ways to get a variety of prebiotics is to consume a diverse diet full of an abundance of different fruits and vegetables, herbs, spices and whole grains.

Prebiotics occur in several plants such as asparagus, sugar beet, garlic, chicory, onion, Jerusalem artichoke, barley, tomato, rye, soybean, peas, legumes, seaweeds and microalgae.

Polyphenol-rich foods such as dark chocolate, olive oil, olives and coffee also have prebiotic effects.10

Prebiotics often found in supplement form include fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin , which help to improve stool consistency, reduce constipation and stimulate the growth of bifidobacterium.11

Probiotics

Fermented foods have a wealth of health benefits to the gut microbiome. Fermented foods are naturally rich in probiotics and have been found to modulate the microbiome and help reduce dysbiosis.

For the best sources of probiotic-rich fermented foods opt for unpasteurized kimchi, pickled foods, kombucha, sauerkraut, kefir, miso and live unpasteurized yoghurt, which are readily available at most supermarkets and health food shops, or you can make your own.11

Live bacteria supplements

Probiotic supplements containing live bacteria have been demonstrated in research to significantly support the gastrointestinal tract through various mechanisms, such as by modulating the gut environment, influencing the composition of the microbiome, enhancing species diversity and supporting the integrity of the intestinal epithelium.

In addition to this, probiotics have been found to promote antimicrobial peptide production, reduce non-commensal bacteria and support healthy immune function.1,12

As discussed, antibiotics can disrupt the gut microflora and these effects can persist over a long period of time. Therefore, it is useful to support a healthy microbiome during and after antibiotic treatment to mitigate these adverse effects.

Recommended product:

- Recovery Biotic – suitable for use alongside antiobiotics, acute and ongoing use.

Key takeaways

- The gut microflora plays an essential role in maintaining health. Studies have demonstrated their importance for immunity, vitamin synthesis, normal digestive function as well as associated reduction in the risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline, to name a few.

- Antibiotics elicit a negative effect on the microbiome which can lead to dysbiosis, leaky gut, increased inflammation and also a higher likelihood of antibiotic resistance.

- Disruption to the microbiome by the use of antibiotics has been shown to increase gastro-intestinal permeability (or leaky gut) and therefore allow the passage of bacteria across the gut epithelial barrier, which can trigger inflammation.

- Fibre and prebiotic foods have been shown to support diversity of the microbiome and therefore should be considered as part of a healthy diet and also during and after antibiotic use.

- Probiotic foods contain live bacteria and are made by fermentation. Consumption of fermented foods such as kefir, kombucha, kimchi, miso, sauerkraut and live natural yoghurt.

- Research has shown live bacteria supplements reduce antibiotic side effects. They have also been shown to support the health of the gut, and immunity and promote a healthy microbiome.

References

- Patangia DV, Anthony Ryan C, Dempsey E, Paul Ross R, Stanton C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen. 2022;11(1):e1260. doi:10.1002/mbo3.1260

- Vidovic N, Vidovic S. Antimicrobial Resistance and Food Animals: Influence of Livestock Environment on the Emergence and Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(2):52. Published 2020 Jan 31. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9020052

- Mills S, Stanton C, Lane JA, Smith GJ, Ross RP. Precision Nutrition and the Microbiome, Part I: Current State of the Science. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):923. Published 2019 Apr 24. doi:10.3390/nu11040923

- Gurung M, Li Z, You H, et al. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine. 2020;51:102590. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.11.051

- Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, De Vos WM. ARTICLE Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun. 2016;7. doi:10.1038/ncomms10410

- Ianiro G, Tilg H, Gasbarrini A. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: Between good and evil. Gut. 2016;65(11):1906-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312297

- Criscuolo D, Srl G, Dominique Dubois IJ, et al. Obesity: A New Adverse Effect of Antibiotics? 2018. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01408

- Blaabjerg S, Artzi DM, Aabenhus R. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in outpatients—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics. 2017;6(4). doi:10.3390/antibiotics6040021

- Kim SK, Guevarra RB, Kim YT, et al. Role of Probiotics in Human Gut Microbiome-Associated Diseases. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;29(9):1335-1340. doi:10.4014/jmb.1906.06064

- Rezac S, Kok CR, Heermann M, Hutkins R. Fermented foods as a dietary source of live organisms. Front Microbiol. 2018;9(AUG). doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01785

- Yadav MK, Kumari I, Singh B, Sharma KK, Tiwari SK. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106(2):505-521. doi:10.1007/s00253-021-11646-8

- Azad MAK, Sarker M, Li T, Yin J. Probiotic Species in the Modulation of Gut Microbiota: An Overview. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018. doi:10.1155/2018/9478630

All of our blogs are written by our team of expert Nutritional Therapists. If you have questions regarding the topics that have been raised, or any other health matters, please do contact them using the details below:

nutrition@cytoplan.co.uk

01684 310099

Find out what makes Cytoplan different

You might also like to read: Is eating organic food better for your gut health?

Last updated on 5th February 2025 by cytoffice

This article is so useful and relevant, especially in today’s climate. Thanks for sharing it.

All very informative and also readable, which is important. I will try to eat and 50 different veg a week, I shall keep a list.

Hi

Thank you for the informative article.

I had to have Metronidazole from the dentist.

I have been eating healthily and taking Fos in the evening and Sacch Boulardi in the morning. How long should I keep taking the Sacch B for please?

Thank you

Hi Janette – Yes take sach boul for about 2 weeks after the antibiotic treatment course has finished and fos for the same time and a further 2 weeks. If you have no symptoms when the courses have been completed then continue as normal, but if you still have symptoms please revert to us for further advice.

Thanks,

Amanda

My husband has just finished aggressive treatment for cancer, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, what supplements should he take to improve his gut health?

We would love to support your husband’s health but would need to make sure we are doing so gently and safely. Could you please get in touch directly with our team of nutritional therapists on nutrition@cytoplan.co.uk, where they will be able to put a protocol together for your husband

I’d love to know the difference between the pro and prebiotic products in a nutshell I take cytobioactive regularly but I see different ones

Are recommended after antibiotics

Hi Nicola,

Thank you for your comment. Probiotics are supplements of live bacteria which are naturally found in the digestive system and are beneficial to health. Prebiotics are fibre which bacteria feed on and it supports the growth of healthy bacteria in gut i.e. they are food for bacteria: examples are FOS, pectin and inulin. Cytobiotic Active is useful to take post antibiotics as you want to replace bacteria that may have been killed. But some products say post-antibiotic as specific strains have specifically demonstrated to support antibiotic associated diarrhoea.

Thanks,

Helen

What’s good after long time on antibiotic medication?

Hello, thank you for your comment. Depending on your individual health needs a mix of probiotics and prebiotics may be beneficial to rebalance the microbiome after long term antibiotic use. If you would like more individual support please contact nutrition@cytoplan.co.uk

Hello. My daughter was on chemo and had to take anti biotics for a year. She finished her chemo 1 year ago. Would it be worth giving her a vitamin/s to help clear her body of the negative effects of the anti biotics and if so what would you recommend? She is 4. I think due to stress I was sick alot which resulted in me being on anti biotics a few times. I had chest infection and scarlet fever to name a few things. Could you recommend anything for me to take to help clear any lingering anti biotics as I know it stays in the body for a while and also improve both of our immune systems.

🙂

Hi Miche,

Thank you for getting in touch and I’m pleased to hear your daughter has completed her chemotherapy. To really help you and your daughter safely and effectively with the foregoing, we need a little more information. We have a health questionnaire which is designed to collect the information we need to give you the best advice. This is downloadable from our website (see here). If you are able to complete and return we can help you both comprehensively. Look forward to hearing from you.

Thanks,

Amanda

Very interesting and it supports a number of health podcasts from the USA

It’s a shame that Doctors are not clued up on this subject.

Hi Carole, the charitable foundation that own Cytoplan, AIM, are currently providing funding to The Nutrition Implementation Coalition which aims to bridge the gap between nutritional knowledge and practice in a number of different health professions – so hopefully the tide is turning.

The article was very helpful indeed, especially for food sources to help the gut. I would have found the picture really helpful, but the writing was too small to read and when I magnified it, it was too distorted and fuzzy. Any chance you can provide a better version as I can print it out to put on the fridge for the family to take the information on board. Thanks

Hello, thank you for your kind comments, we are glad you found the information useful. Please email into nutrition@cytoplan.co.uk and we can send the diagram over to you.