Our blog this week comes in two parts, with the second to follow next week, written by Miguel Toribio-Mateas. Miguel is an experienced nutrition practitioner and researcher with a specialisation in ageing and particularly brain ageing, having completed a MSc in Clinical Neuroscience at Roehampton University along with extensive professional development in this subject, including a fellowship in metabolic and nutritional medicine with the Metabolic Medicine Institute (US) and a US Board Certification in Clinical Science of Anti-Ageing.

Miguel has recently been awarded a Santander Bank Scholarship for multidisciplinary doctoral research at the Institute for Work-Based Learning of Middlesex University. His Professional Doctorate research project is on translational medicine in brain ageing and cognitive decline, using the Bredesen Protocol as a model for neuroprotection.

You may also know Miguel from his voluntary role as Chairman of the British Association for Applied Nutrition and Nutritional Therapy. He is also a regular contributor to professional publications and is quoted in national/international press frequently on health and nutrition matters. Last but not least, Miguel is a born and bred Mediterranean man (although adopted British) so we trust his “insider view” on the beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet.

The Mediterranean diet is a “trending topic”. Everyone is talking about it and everyone seems to claim that the diets they’re recommending are based upon, or modelled upon, a Mediterranean-type diet. Obviously, some of these claims are more credible than others, and as a Mediterranean man myself, I can’t help but smile at some of them. There are as many variations of this so-called Mediterranean diet as there are of a vegan or a vegetarian diet. Every country around the Mediterranean Sea will have its own “version” of it, which is likely to include a lot of foods that are seen in typical Mediterranean diet “pyramids” or charts, and a lot that are totally ignored by scientists who specialise in this specific topic.

The images of foods that the romanticised idea of the Mediterranean diet tend to conjure up include oily fish, lots of green vegetables, fruit and olive oil. One cannot help but think of the typical picture of red tomatoes and a few basil leaves alongside some fresh pasta. But is this the true Mediterranean diet, and does everyone around the Mediterranean eat like that? The reality is that any model that aims to deal with a large amount of complexity, like variations between regions inside each of the Mediterranean countries, is likely to need to be oversimplified to make any sense at all. Thus the Mediterranean diet “model” ignores the fact that cured and organ meats are eaten daily in some regions of Spain and Italy, as is full fat dairy, but the whole variety issue is perhaps a subject best left for another blog. Today I’d like to focus on what I believe to be the key nutrients in the Mediterranean diet that act as neuroprotective agents, i.e. natural substances present in food consumed around the Mediterranean that are known to enhance cognitive function and to delay brain ageing.

What current literature is saying about nutrition and brain ageing

I’m using a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Lopes da Silva et al (2014) because 1) it’s an open access article (I’m a great believer in democratising access to science for everyone, and not just an elite) and 2) because it provides a comprehensive correlation between the adequacy of various nutrients and brain function in Alzheimer’s disease (AD henceforth) patients. Fortunately, not everyone gets Alzheimer’s, but because there is a lot of research on this condition, and particularly on the nutrient deficiencies that are characteristic of its progressive development, I find a review of this type really useful to use as a “guideline” for nutrients that contribute to healthy brain function. These include the vitamins A, C, D and E, as well as the methyl donors B12 (cobalamin), B6 (pyridoxine) and folate, plus B1 (thiamin), the minerals manganese, calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, selenium and zinc, and the essential fatty acids DHA (Docosahexaenoic acid) and EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid). Lower levels of all these nutrients are found in the blood of individuals suffering from AD and are indicative of their impaired systemic availability, which puts these individuals at further risk of neurodegeneration.

So why do I see the above systematic review relevant, you may be asking

Well, aside from the robustness of the methodology employed by the review, the multi-supplementation model investigated as part of the meta-analysis features all of the nutrients that are naturally occurring in the Mediterranean diet. Despite the fact that this dietary model can’t cope with the amount of the intraregional variations around the Mediterranean (they would make any statistics package explode!) the Mediterranean diet can be described broadly as the dietary practices of inhabitants in regions around the Mediterranean Sea, e.g., Italy, Spain, Greece, Croatia, Turkey, Morocco, etc. Just reading the names will give you an idea of the variety of this overarching dietary umbrella that is characterised by the presence of high levels of fresh vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds and whole grains, as well as fresh fish (including oily fish like sardines, anchovies, mackerel, etc.), seafood and reduced amounts of meat compared to other Western diet types.

Other typical features of the Mediterranean diet include the regular consumption of pulses (e.g. lentils, chickpeas, beans), fresh dairy produce and moderate red wine consumption. The Mediterranean diet is naturally rich in vitamins with antioxidant properties such as vitamins A, K, C, E and D, as well as in methyl donors such as folate and vitamins B6 and B12. Additionally, the Mediterranean diet is also one of the richest dietary patterns in polyunsaturated omega-3 (ω-3) fatty acids (PUFAs) and polyphenolic compounds. Of particular relevance are the myriad of antioxidant compounds in olive oil, which are well documented to possess anti-inflammatory effects and to aid with the clinical management of a variety of conditions.

A “good” Mediterranean diet is highly anti-inflammatory

Like all “diets” the Mediterranean diet can be exemplarily healthy or absolutely terrible. As a Spaniard who’s lived in the UK for 22 years I am concerned that the latest wave of interest in the Mediterranean diet will lead to it being idealised or romanticised. Some have even claimed that the Eatwell Guide is mapped on the Mediterranean guide, which I absolutely fail to see. Is it just me? However, there’s no denying that a relatively lower-starch, green vegetable, olive oil and nut-rich Mediterranean dietary pattern has long been correlated with lower levels of pro-inflammatory proteins such as CRP (C-reactive protein), a very accessible (low cost and widely available) biomarker of systemic inflammation, including neuroinflammation. This type of “low carb” Mediterranean diet also helps bring down levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-10; lowers lipid peroxidation, measured by means of assessment of malondialdehyde levels in urine, plus reduces DNA damage, assessed by looking at blood levels of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHGH). It is believed that the high amount of naturally-occurring polyphenols in a Mediterranean-type diets accounts for the improvement in DNA repair capacity.

A “good” Mediterranean diet is high in fat

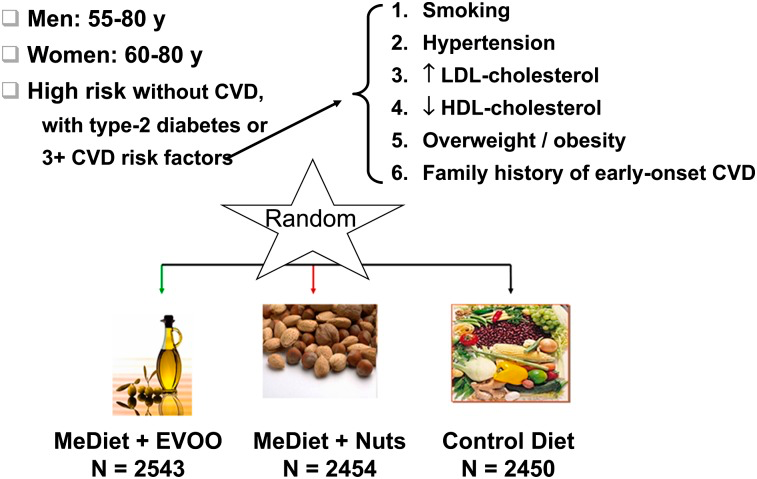

Perhaps one of the most interesting realisations about the Mediterranean diet is that it’s actually pretty high in fat compared with other diets. In fact, some key trials that have been designed to assess the impact on a Mediterranean style of eating versus a control have focused on the effects of fats, and particularly fats from fish, nuts and olive oil. One such study is the PREDIMED study (Ros, E. et al, 2014), which looked at traditional risk factors in the development of atherosclerosis, the basis for cardiovascular disease (CVD), such as cholesterol levels, both LDL (known as “bad”) and HDL (known as “good”) cholesterol.

The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) study is a multicenter, randomised, primary prevention trial designed to assess the long-term effects of the Mediterranean diet without counting calories or cutting portion sizes (aka energy restriction) on cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidents in individuals at high risk. The study took place over a space of 5 years and randomly assigned all participants to one of 3 diet groups:

- MeDiet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO);

- MeDiet supplemented with nuts; and

- a control diet (simply consisting of advice on a low-fat diet).

Whilst the PREDIMED study doesn’t look at any groundbreaking factors, I find it highly relevant here because it acknowledges that it is the oxidation of cholesterol, and not just cholesterol levels per se, that contribute to endothelial dysfunction, by means of increased oxidative stress and inflammation. Increased LDL cholesterol is a potent atherogenic factor, but it is oxidatively modified LDL particles that are critical in the onset of atherosclerosis; one of the CVD incidents that PREDIMED reports a decreased risk of after just 3 months of a diet rich in olive oil or nuts. Oxidation and inflammation are events that contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases when they’re sustained over time, so the reduction in inflammatory molecules demonstrated after 3 months on a Mediterranean diet rich in olive oil or rich in nuts can only be interpreted as being neuroprotective. Additionally, emerging evidence points to the synergy amongst the various fat molecules, i.e. the combination of omega / ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) from nuts and oily fish, the oleic acid (a monounsaturated omega / ω-9 fatty acid), and other cardio- and neuroprotective phenolic compounds such as hydroxytyrosol and oleocanthal which seem to work better together than as individual agents. Particularly, hydroxytirosol has been shown to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis, the growth of new mitochondria, the power plants that provide cellular energy in every cell in the body. Hydroxytyrosol has also been seen to improve cellular repair and defence mechanisms, thereby improving genomic integrity, a key feature of the Mediterranean diet that I’ll be covering in more detail in a second blog very soon.

Design of the PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) study. CVD, cardiovascular disease; EVOO, extra-virgin olive oil; MeDiet, Mediterranean diet. Reproduced from Adv Nutr. 2014 May; 5(3): 330S–336S.

So what do we know about the Mediterranean diet so far?

I hope that having read this blog you’ve learned that there isn’t just one Mediterranean diet, but that the components that are shared across diets in Mediterranean countries make this type of diet highly anti-inflammatory. Mediterranean diets are also pretty high in fat, but they contribute to cardiovascular health. And because there’s an important vascular element they contribute to brain health, they’re neuroprotective by proxy. In a second blog I’ll be exploring how the Mediterranean diet provides an ideal model for multi-supplementation that’s naturally occurring, well documented and with a range of beneficial actions. Specifically, I’ll be reviewing the evidence that many of the individual “ingredients” in the Mediterranean diet actually work as brain “anti-ageing” agents.

The second part to this blog will be published next week and will look at individual vitamins, minerals and plant bioactives characteristic of the Mediterranean diet which can provide a naturally occurring model for multi-supplementation for a nutrient-depleted Western diet

Miguel Toribio-Mateas

Miguel is a nutrition practitioner, author and researcher with extensive knowledge and expertise in functional medicine and ageing science.

References:

Lopes Da Silva, S., Vellas, B., Elemans, S., Luchsinger, J., Kamphuis, P., Yaffe, K., Sijben, J., Groenendijk, M. & Stijnen, T. (2014) Plasma nutrient status of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement, 10(4) pp. 485-502.

Open access available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24144963

Ros, E., Martínez-González, M. A., Estruch, R., Salas-Salvadó, J., Fitó, M., Martínez, J. A. & Corella, D. (2014) Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health: Teachings of the PREDIMED Study. Advances in Nutrition, 5(3) pp. 330S-36S.

Open access available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4013190/

Related Cytoplan blogs

The Mediterranean diet: a naturally occurring model of multi-supplementation – Part 2

Mediterranean diet cuts heart and stroke risk

Official guidelines on fat intake: “Are we in need of a major overhaul”?

With many thanks to Miguel for this article. If you have any questions regarding the topics that have been raised, or any other health matters please do contact me (Amanda) by phone or email at any time.

amanda@cytoplan.co.uk, 01684 310099

Amanda Williams and the Cytoplan Editorial Team: Miguel Toribio-Mateas, Clare Daley, and Jo Doverman

Last updated on 27th September 2016 by cytoffice

Hello,

I am an interested layman (lady) in healthy eating. I have read and researched a great deal over my 58 years of life on the topic. I try to follow as many guide lines as I can, but as you know, there are many trends that are proclaimed as healthy, only to be shot down a few years later as of no benefit. It is a difficult pathway to pick through.

I thought the information above was very informative and luckily for me, most of the guidelines have already been included in my diet quite some years ago.

My one suggestion would be if this sort of information could be put into layman’s terminology as a lot of the scientific / medical terms were beyond me. I was able to glean the gist of what he was saying, but that is only because I have read up on the subject over the years. Most non professional people reading it, wouldn’t have that benefit. Miguel stated that he likes “open access information” but you have to be able to understand the information for it to be truly open access. If it ‘goes over your head’, then the message fails.

Please simplify for all us simpletons out there!!

Kind regards,

Sue

Well said Sue I couldnt understand a word of it and now am confused as to is a Mediterranean diet good for you or not?

I concur with Sue. I consider myself “reasonably” intelligent, but l found some of the very interesting article, hard to fully understand for the average lay person! Paul.

Thank you to everyone for taking the time to share your thoughts on our latest blog post.

Whilst we appreciate that not all of our readers are health professionals, it is sometimes difficult to get the perfect balance with our articles, especially when explaining a somewhat complicated topic such as The Mediterranean Diet. We acknowledge that there is quite a heavy technical element to this blog post which some readers may have difficulty understanding.

Miguel will be addressing these queries in the second part of his fascinating blog, this Thursday. We’re really looking forward to sharing more on the subject and we hope it will help clear up any questions you may have.

Many thanks,

The Cytoplan Editorial Team

I agree with Sue , laymans terms would be easier to follow , I do understand though that this blog is for health professionals !

Basically, eat less junk, eat more fresh fruit and veggies , nuts and olive oil. Cannot agree necessarily with eating more fish, stocks are low, overfished and many are full of heavy metals…or at least that is the information I have read, who knows, so much truth isn’t “truth”.

Thankyou , and kind regards

Helen

I think a good lay summary would be that the diet is high in fruits, vegetables and some (not excessive) wholegrains. But also one that is high in fat from polyunsaturated sources such as nuts, fresh fish and is high in the mono unsaturated fats found in olive oil.

Which is incidentally what we could recommend for good eye health also.

Hope this helps,

Iain

Here, here, l’m not stupid, but I found the article difficult to understand!

Thank you everyone, for taking the time to share your thoughts on our latest blog post.

The blog is read by both health professionals as well as lay people with an interest in health and well-being and sometimes it is difficult to balance the level of information to provide interest to both. We acknowledge that there is quite a heavy technical element to this blog post which some readers may have difficulty understanding.

Miguel will be addressing these queries in the second part of his fascinating blog, this Thursday. We’re really looking forward to sharing more on the subject and we hope it will help clear up any questions you may have.

Many thanks,

The Cytoplan Editorial Team

I agree Sue, a silly article.

I found this article to be very good, and although I got a bit lost with some of the very long words, I do think I got the gist. As a vegan I think I follow this diet quite closely, but although I supplement with flax seed oil to try to get a better balance, I do miss out on fats. And without a personal nutritionalist it’s difficult to know exactly what to do. I look forward to Part 2!

Thank you David, for taking the time to share your thoughts on our latest blog post.

Whilst we appreciate that not all of our readers are health professionals, it is sometimes difficult to get the perfect balance with our articles, especially when explaining a somewhat complicated topic such as The Mediterranean Diet. We acknowledge that there is quite a heavy technical element to this blog post which some readers may have difficulty understanding.

Miguel will be addressing these queries in the second part of his fascinating blog, this Thursday. We’re really looking forward to sharing more on the subject and we hope it will help clear up any questions you may have.

Many thanks,

The Cytoplan Editorial Team

I think it’s difficult to know how lay to make things, because if you’re in an environment where everyone knows the terms and is on the same level then quite difficult things sound lay… And making it easier can cross into patronising.

I thought it was a brilliant article and I look forward to the second installment.

Iain, I agree with you. If something sounds patronising it will surely turn people off. I love science but the BBC science television show Horizon generally treats people like half-wits who must have the same information told to them very slowly, more than once, preferably by someone in a car driving across the Nevada desert to the accompaniment of loud music. It drives me crazy. I appreciate that communicating important information must be very difficult, not appearing to talk down to people yet at the same time not talking over their heads.

Haha and I thought I was the only one who hated the horizons programs! Glad I’m not alone.

My latest pet hate is the program with Greg Wallace about eating for less. Because convenience food is just the same as home made, and ready meals are perfectly healthy. Cheers Greg, really working out for the UK population that is.

I thought this was a brilliant article even though most of the highly specialist terminology was beyond me. At least it demonstrates there is a profound scientific underpinning to the arguments advanced which other scientists can agree with or challenge. Knowing there is a second article that will address the queries is reassuring. Thank you.

Robina

Excellent article. I am particularly interested in nutrition for older people – I work with people with Alzheimer’s and this a field that needs addressing in nursing homes as well as in the community.

Great article look forward to part 2 🙂

Hi Jackie,

Thank you for your comment. Part 2 is available here.

Best wishes,

Abbey