Sleep is fundamental for health and regeneration and the healthy production and balance of hormones. Adults aged 18 to 64 need to sleep for 7 – 9 hours a night, but sleep disturbances are reported by nearly one third of the general population across all age groups, and further increase with advancing age, affecting nearly 50% of individuals over the age of 651. As they age, women are more likely to suffer with sleep disturbances such as insomnia, poor sleep quality and sleep deprivation than men.

During menopause transition, there is often an emergence of physiological and psychological symptoms such as hot flashes, mood changes, vaginal dryness and sleep disturbance.

Many women experience such symptoms during and following menopause transition, and studies show that 60-86% of women experience symptoms so bothersome that they seek medical care.

However, after doing so, many women feel misunderstood and disappointed that their concerns haven’t been addressed – and as a result, many will go on to pursue natural treatments.

In fact, about half of women in the menopause transition favour complementary and alternative medicine treatments2.

Sleep disturbances are a major complaint of women transitioning through menopause and can have a far-reaching impact on quality of life, mood, productivity and physical health1.

Sleep disturbance is also common in postmenopausal women3, with some studies showing that up to half of women experiencing a dramatic increase in sleep disturbance during the transition from perimenopause to menopause.

Some studies also show that as many as 42% of women will develop chronic insomnia by the end of their menopause transition.4

We are going to explore menopause and insomnia further in this blog.

What is menopause and menopause transition?

Perimenopause, or the menopause transition, is a natural progression in a woman’s life when her reproductive system gradually slows until she hits “menopause”; when she has had an absence of periods for 12 months.

The length of perimenopause differs between individuals, and can occur over just a few months, or up to 10 years – but 4 years is the average duration.

Natural menopause results from a decrease in ovarian function and changes in reproductive hormone levels as the ovaries become less responsive to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH), leading to reduced circulating levels of oestrogen and progesterone5.Due to a negative feedback mechanism, FSH and LH increase as the ovarian hormones oestrogen and progesterone decline.

In 2021 an estimated 1.02 billion women were postmenopausal globally, with 1.65 billion anticipated by 20506.

Defining sleep disturbance and insomnia

The term sleep disturbance describes subjectively perceived sleep problems that don’t necessarily meet the criteria for a clinical disorder, despite being bothersome for the individual.

In contrast, insomnia is a clinically defined disorder, diagnosed when an individual reports the following criteria7:

- Difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, or experiencing nonrestorative sleep, despite adequate opportunity

- Daytime functional impairments resulting from nocturnal sleep disturbance

A substantial number of women experience sleep difficulties during the menopause transition, and then through menopause and beyond, with around 26% experiencing severe symptoms that impact their ability to function in the daytime, which is diagnosed as insomnia8.

Studies have shown that the incidence rates of sleep problems are 39–47% in peri-menopausal and 35–60% in postmenopausal women, compared to just 16–42% in premenopausal women9.

Pathophysiology of menopausal sleep disturbances

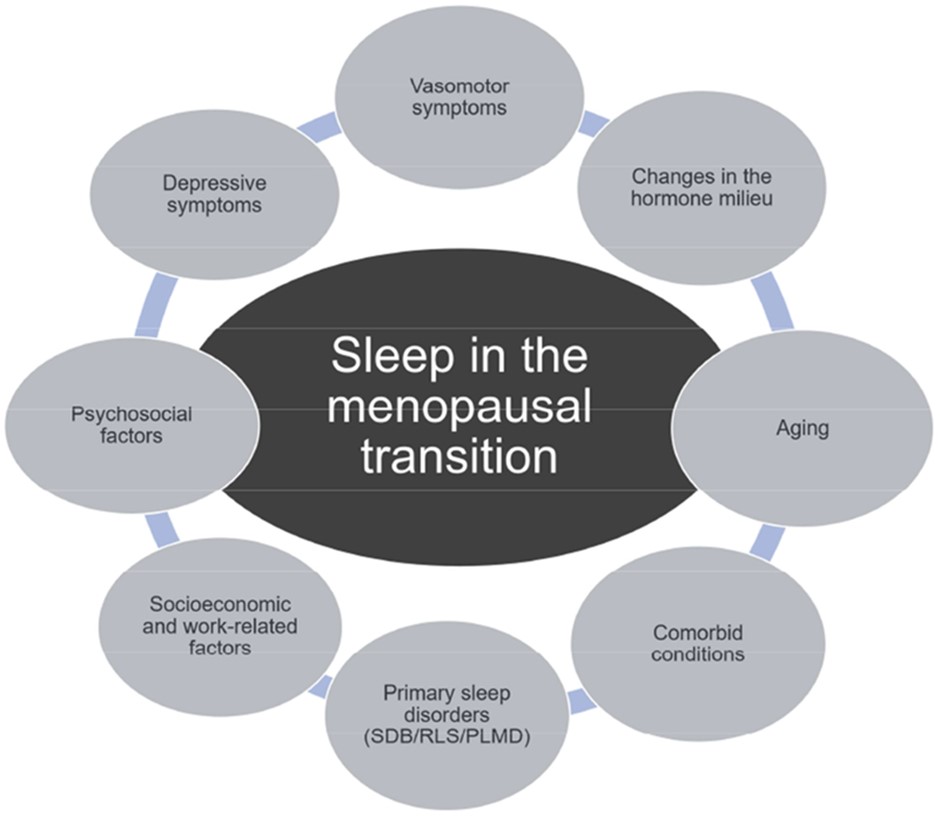

The pathophysiology of sleep disturbance during the menopausal period is multifactorial, and we will examine some of the possible contributing factors below. Several of these factors may also interact with each other – creating a challenge when trying to determine the primary cause of sleep disturbance.

When we also consider that some factors may interact to worsen sleep quality, such as several sleep disorders, we highlight the need for a therapeutic strategy that supports the whole person10.

Figure: Sleep in the menopausal transition10. SDB, sleep-disordered breathing; PLMD, periodic limb movement disorder; RLS, restless legs syndrome

Changes to reproductive hormones

In addition to menopause, it has been reported that women have specific periods related to vulnerability to sleep disorders, such as puberty, menstruation and pregnancy, suggesting a close link between sleep disorders and female hormones – and insomnia is closely related to hormonal changes11.

Female hormones can have a beneficial effect on sleep, so falling levels through menopause transition and after menopause are likely to be responsible, at least in part, for sleep disturbance during this time.

Oestrogen blocks wake-promoting neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, histamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine12. It increases the rapid eye moment (REM) sleep, total sleep time and decreases sleep latency and spontaneous arousals. It is also known to have a thermoregulatory effect at night, which can indirectly improve sleep13.

Reductions in oestradiol, the most potent form of oestrogen have been associated with difficulties with both falling and staying asleep14, as well as sleep-disordered breathing and a high frequency of movement arousals15.

During the menopausal transition, declining or low progesterone levels, resulting from the failure of a growing follicle to reach sufficient maturation for ovulation, are associated with sleep disturbances.

Progesterone stimulates benzodiazepine receptors, causing the release of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a sedating neurotransmitter12. Low levels of progesterone have been linked to increased sleep-disordered breathing and a higher frequency of sleep disturbances and insomnia15.

Higher levels of FSH, as observed in peri-menopausal and menopausal women, have been linked to poor sleep efficiency, lower levels of deep sleep and subjective sleep quality, whereas higher LH levels have been associated with lower sleep efficiency and higher numbers of awakenings15.

Age and sleep quality

On the whole, women have a better quality of sleep as compared to men, which is evident by longer sleep times, shorter sleep-onset latency, and higher sleep efficiency. Despite all this, women generally tend to have more sleep-related complaints than men.

However, it is important to note that the amount of slow-wave sleep slowly declines with age both in men as well as women. Ageing is independently associated with sleep fragmentation, insomnia symptoms, circadian rhythm disruption, lighter sleep and reduced sleep efficiency16.

Our circadian rhythm is an internal body clock which initiates various physiological processes. The circadian clock undergoes many changes throughout life, at both physiological and molecular levels.

Melatonin, synthesised in the pineal gland, also regulates the circadian rhythm by detecting changes in the length of day and night or seasonal sunlight hours. Endogenous secretion of melatonin decreases with age and varies with gender, and in menopausal women, is associated with a significant reduction in melatonin levels, thus affecting sleep patterns17.

Vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes)

Hot flushes, a sensation of heat, sweating, anxiety and chills lasting between 3 and 10 minutes, are a hallmark of the menopause transition, being reported by up to 80% of women18.

Hot flushes can occur in the day, or the nighttime (night sweats) and the presence of hot flushes is consistently associated with poorer self-reported sleep quality and chronic insomnia, indicating that women link night sweats to waking in the night8.

While not all hot flushes are associated with disturbed sleep, there is a strong overlap in timing between hot flush onset and awakenings, which suggests that these events may be driven by a common mechanism within the central nervous system in response to fluctuating oestrogen levels, or that sweating triggered by a hot flush can contribute to, or extend, the interval of waking19.

It should be noted that not all women who experience sleep disturbance in menopause complain of hot flushes, so it is important to consider other factors that may be contributing to their symptoms.

Mood disorders and sleep

Mood disorders become more common in ageing women and may disrupt sleep. A number of studies have demonstrated that the rate of depression increases at least twofold during the menopause transition, independent of other known factors20,21.

Depression and anxiety are associated with poor sleep, as well as with vasomotor symptoms, in complex, multidirectional interactions. It is suggested that hot flushes disrupt sleep, intrusive anxious thoughts during nocturnal awakenings trigger daytime mood symptoms (domino effect), and depression links with insomnia, in a vicious cycle22.

Other factors that may worsen sleep quality

Other common sleep disorders that may exacerbate sleep disturbances in menopause include restless leg syndrome (RLS). RLS is characterised by an urge to move the legs during period of rest or inactivity and typically has a circadian pattern with increasing severity at night.

RLS is considered a sleep disorder because deliberate limb movements initiated to provide relief from RLS discomfort delay the onset of sleep. RLS appears to have a slight female predominance, and studies suggest that during times of hormonal alterations, women are predisposed to RLS and other sleep disorders. Individuals with RLS frequently report sleep-onset insomnia and subsequent daytime sleepiness and fatigue7.

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing has been observed in 47-67% of postmenopausal women. The combination of weight gain and increased waist to hip ratio after menopause leads to changes in the upper airway and contributes to OSA and other sleep disorders23.

The role of the microbiome in perimenopause and menopause

Perimenopause and menopause are often associated with dysbiosis and gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. Oestrogen levels can affect the gut microbiota, and the microbiome, in turn can affect serum oestrogen levels as certain microbes in the gut (known as the estrabolome) secret beta-glucuronidase; a bacterial enzyme that deconjugates oestrogens into their active forms, which can then be reabsorbed through the intestine and re-enter the blood stream24 – which suggests that the composition of the gut bacteria plays a role in the onset an progression of some menopause related symptoms.

Nutrition in menopause – supporting sleep and beyond

There are a number of key nutrients that are essential to support optimal health through menopause transition and following menopause:

Probiotics

These live beneficial bacteria, including those belonging to the lactobacilli and bifidobacteria strains have displayed evidence of improving sleep quality and stress25 and improvements in the self-reported parameter of sleep quality and disturbance26.

Pro- and prebiotics can also be used in conjunction with menopause hormone therapy and may attenuate the side effects that can arise from hormone replacement27.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin which is synthesised by the body through UV-B radiation in the summer months. With ageing, the rate of hydroxylation of vitamin D precursors in the body decreases, so the importance of exogenous vitamin D intake increases. Routine supplementation from October-March is recommended, at a dose of 2000IU per day, taken with meals.

Vitamin D status is a primary influencer of the absorption of calcium, so plays an important role in protecting bone density28. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with sleep disorders and poor sleep quality, and supplementation has been proposed as a therapeutic option to improve sleep quality29.

B Vitamins

B vitamins play an important role in menopause, through the processing of carbohydrates and the functioning of the immune system. Adequate B vitamin intake significantly reduces levels of homocysteine, high levels of which are associated with osteoporosis and increased risk of bone fracture. Folic acid, and vitamins B6 and B12, along with magnesium and zinc are cofactors in melatonin synthesis, so adequate intake of these nutrients is necessary for good sleep30.

Isoflavones

Isflavones ae phytochemicals which are abundant in soybeans. Active isoflavones found in soy include daidzein, glycitein and genistein. They are considered to be phytoestrogens, and thereby elicit a mild oestrogenic effect.

Phytoestrogens can weakly occupy oestrogen receptors within the body and stimulate a gentle oestrogenic response and may alleviate several of the symptoms associated with menopause31.

Studies have also demonstrated that daily isoflavone intake may have a beneficial effect on sleep duration and quality32,33.

L-Theanine

A key ingredient in tea leaves, is often referred to as “the calming amino acid”. Theanine can increase alpha brain waves and the relaxing neurotransmitter GABA, but also acts as a precursor to serotonin – which is required for melatonin production; the sleep hormone and is central to controlling sleep and wake cycles34.

Magnesium

Magnesium is the second most abundant mineral in the body and serves as a cofactor for several enzymatic reactions. Magnesium may play a role in sleep by activating GABA, and a deficiency can contribute to low levels of melatonin. Supplementing with magnesium can decrease the concentration of the stress hormone, resulting in a calmer central nervous system and potentially better sleep35.

In Magnesium Bisglycinate, magnesium is bound to the amino acid glycine, which itself has the property to enhance the quality of sleep and neurological functions – so this form of magnesium may be particularly supportive for sleep36.

Lifestyle considerations to help with sleep quality during menopause

Reflexology

Along with yoga, walking and aromatherapy massage have all demonstrated a significant impact on decreasing insomnia and depression in menopausal women37.

Accupuncture

This therapy is associated with a significant reduction in symptoms for women experiencing menopause-related sleep disturbances and has been suggested to be adopted as part of a multimodal approach for improving insomnia in menopause38.

Music

Listening to music regularly has been shown to reduce levels of depression as well as improving sleep quality in menopausal women39.

Regular exercise

Exercising at least 3 times a week, for 30-60 minutes has been shown to have beneficial effects on sleep quality and insomnia symptoms in perimenopausal women40. As well as improving sleep, increased physical activity can support improvements in cardiometabolic, physical and psychosocial health during menopause41.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

For insomnia, CBT is a treatment that can change patients’ beliefs and attitudes about sleep and behavioural techniques to improve their insomnia. In menopause, CBT has proven to be an effective therapy at significantly improving sleep as well as the interference of hot flushes on sleep and reducing depressive symptoms42,43.

…and here are some more tips to support a restful night’s sleep:

- Take a warm/hot Epsom salt (a handful) bath before bed to aid sleep and relaxation. Hot baths bring blood vessels to the surface allowing your core body temperature to cool which helps the body prepare for sleep as body temperature begins to drop during night

- Ensure daytime full light exposure as well as activity, take a run or walk during daylight hours to top up on serotonin and vitamin D. Ensure you don’t exercise too late in the evening as can delay sleep onset

- Keep noises down (earplugs might help)

- Keep the room cool. Most people sleep best at around 18oC with adequate ventilation

- Make sure the bed is comfortable. Waking often with a sore back or neck suggests the mattress or pillow may need changing

- Create an aesthetic environment that encourages sleep – use serene and restful colours and eliminate clutter and distraction

- Avoid work or watching television in bed

- Consider using a relaxation, meditation or guided imagery app, any of these may help with getting to sleep and will certainly help with relaxation

- Cut down on caffeine. Ideally no caffeine after midday – some people take 12 hours to metabolise caffeine.

- Disturbance to sleep is one of the most common symptoms experienced during menopause transition and post-menopausally

- The pathophysiology of sleep disturbance during menopause is multifactorial and in part due to hormonal changes and advancing age, but also intertwined with other menopausal symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms and mood imbalance

- Other sleep disorders such as restless leg syndrome and obstructive sleep apnoea are also common around this stage of life

- The microbiome can also affect the occurrence of menopausal symptoms

- There are a number of nutritional and lifestyle factors that have shown to support sleep during the menopause transition and after menopause

References

- Haufe A, Leeners B. Sleep Disturbances Across a Woman’s Lifespan: What Is the Role of Reproductive Hormones? J Endocr Soc. 2023 Mar 15;7(5):bvad036. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvad036. PMID: 37091307; PMCID: PMC10117379.

- Management of perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms. BMJ. 2023 Nov 13;383:p2636. doi: 10.1136/bmj.p2636. Erratum for: BMJ. 2023 Aug 8;382:e072612. PMID: 37957013.

- Jeon GH. Insomnia in Postmenopausal Women: How to Approach and Treat It? J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 12;13(2):428. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020428. PMID: 38256562; PMCID: PMC10816958.

- Ciano C, King TS, Wright RR, Perlis M, Sawyer AM. Longitudinal Study of Insomnia Symptoms Among Women During Perimenopause. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017 Nov-Dec;46(6):804-813. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.07.011. Epub 2017 Sep 5. PMID: 28886339; PMCID: PMC5776689.

- Yelland S, Steenson S, Creedon A, Stanner S. The role of diet in managing menopausal symptoms: A narrative review. Nutr Bull. 2023 Mar;48(1):43-65. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12607. Epub 2023 Feb 15. PMID: 36792552.

- United Nations Population Division. World Population Prospects. 2021. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/12/18/2022

- Joffe H, Massler A, Sharkey KM. Evaluation and management of sleep disturbance during the menopause transition. Semin Reprod Med. 2010 Sep;28(5):404-21. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262900. Epub 2010 Sep 15. PMID: 20845239; PMCID: PMC3736837.

- Baker FC, de Zambotti M, Colrain IM, Bei B. Sleep problems during the menopausal transition: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018 Feb 9;10:73-95. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S125807. PMID: 29445307; PMCID: PMC5810528.

- Kravitz HM, Zhao X, Bromberger JT, Gold EB, Hall MH, Matthews KA, Sowers MR. Sleep disturbance during the menopausal transition in a multi-ethnic community sample of women. Sleep. 2008 Jul;31(7):979-90. Erratum in: Sleep. 2008 Sep 1;31(9):table of contents. PMID: 18652093; PMCID: PMC2491500.

- Chen LR, Chen KH. Utilization of Isoflavones in Soybeans for Women with Menopausal Syndrome: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 22;22(6):3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063212. PMID: 33809928; PMCID: PMC8004126.

- Lee KA, Baker FC. Sleep and Women’s Health Across the Lifespan. Sleep Med Clin. 2018 Sep;13(3):xv-xvi. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.06.001. Epub 2018 Jul 3. PMID: 30098760.

- Jeon GH. Insomnia in Postmenopausal Women: How to Approach and Treat It? J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 12;13(2):428. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020428. PMID: 38256562; PMCID: PMC10816958.

- Tandon VR, Sharma S, Mahajan A, Mahajan A, Tandon A. Menopause and Sleep Disorders. J Midlife Health. 2022 Jan-Mar;13(1):26-33. doi: 10.4103/jmh.jmh_18_22. Epub 2022 May 2. PMID: 35707298; PMCID: PMC9190958.

- Gava G, Orsili I, Alvisi S, Mancini I, Seracchioli R, Meriggiola MC. Cognition, Mood and Sleep in Menopausal Transition: The Role of Menopause Hormone Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019 Oct 1;55(10):668. doi: 10.3390/medicina55100668. PMID: 31581598; PMCID: PMC6843314.

- Haufe A, Leeners B. Sleep Disturbances Across a Woman’s Lifespan: What Is the Role of Reproductive Hormones? J Endocr Soc. 2023 Mar 15;7(5):bvad036. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvad036. PMID: 37091307; PMCID: PMC10117379.

- Pengo MF, Won CH, Bourjeily G. Sleep in Women Across the Life Span. Chest. 2018 Jul;154(1):196-206. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.005. Epub 2018 Apr 19. PMID: 29679598; PMCID: PMC6045782.

- Pines A. Circadian rhythm and menopause. Climacteric. 2016 Dec;19(6):551-552. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2016.1226608. Epub 2016 Sep 2. PMID: 27585541.

- Tepper PG, Brooks MM, Randolph JF Jr, Crawford SL, El Khoudary SR, Gold EB, Lasley BL, Jones B, Joffe H, Hess R, Avis NE, Harlow S, McConnell DS, Bromberger JT, Zheng H, Ruppert K, Thurston RC. Characterizing the trajectories of vasomotor symptoms across the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016 Oct;23(10):1067-74. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000676. PMID: 27404029; PMCID: PMC5028150.

- de Zambotti M, Colrain IM, Javitz HS, Baker FC. Magnitude of the impact of hot flashes on sleep in perimenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2014 Dec;102(6):1708-15.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.016. Epub 2014 Sep 23. PMID: 25256933; PMCID: PMC4252627.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Boorman DW, Zhang R. Longitudinal pattern of depressive symptoms around natural menopause. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Jan;71(1):36-43. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2819. PMID: 24227182; PMCID: PMC4576824.

- Bromberger JT, Matthews KA, Schott LL, Brockwell S, Avis NE, Kravitz HM, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, Sowers M, Randolph JF Jr. Depressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). J Affect Disord. 2007 Nov;103(1-3):267-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.034. Epub 2007 Feb 28. PMID: 17331589; PMCID: PMC2048765.

- Thurston RC, Bromberger JT, Joffe H, Avis NE, Hess R, Crandall CJ, Chang Y, Green R, Matthews KA. Beyond frequency: who is most bothered by vasomotor symptoms? Menopause. 2008 Sep-Oct;15(5):841-7. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318168f09b. PMID: 18521049; PMCID: PMC2866103.

- Salari N, Hasheminezhad R, Hosseinian-Far A, Rasoulpoor S, Assefi M, Nankali S, Nankali A, Mohammadi M. Global prevalence of sleep disorders during menopause: a meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2023 Oct;27(5):1883-1897. doi: 10.1007/s11325-023-02793-5. Epub 2023 Mar 9. PMID: 36892796; PMCID: PMC9996569.

- Ervin SM, Li H, Lim L, Roberts LR, Liang X, Mani S, Redinbo MR. Gut microbial β-glucuronidases reactivate estrogens as components of the estrobolome that reactivate estrogens. J Biol Chem. 2019 Dec 6;294(49):18586-18599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010950. Epub 2019 Oct 21. PMID: 31636122; PMCID: PMC6901331.

- Haarhuis JE, Kardinaal A, Kortman GAM. Probiotics, prebiotics and postbiotics for better sleep quality: a narrative review. Benef Microbes. 2022 Aug 3;13(3):169-182. doi: 10.3920/BM2021.0122. Epub 2022 Jul 11. PMID: 35815493.

- Santi D, Debbi V, Costantino F, Spaggiari G, Simoni M, Greco C, Casarini L. Microbiota Composition and Probiotics Supplementations on Sleep Quality-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clocks Sleep. 2023 Dec 13;5(4):770-792. doi: 10.3390/clockssleep5040050. PMID: 38131749; PMCID: PMC10742335.

- Barrea L, Verde L, Auriemma RS, Vetrani C, Cataldi M, Frias-Toral E, Pugliese G, Camajani E, Savastano S, Colao A, Muscogiuri G. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Any Role in Menopause-Related Diseases? Curr Nutr Rep. 2023 Mar;12(1):83-97. doi: 10.1007/s13668-023-00462-3. Epub 2023 Feb 7. PMID: 36746877; PMCID: PMC9974675.

- Takács I, Dank M, Majnik J, Nagy G, Szabó A, Szabó B, Szekanecz Z, Sziller I, Toldy E, Tislér A, Valkusz Z, Várbíró S, Wikonkál N, Lakatos P. Magyarországi konszenzusajánlás a D-vitamin szerepérol a betegségek megelozésében és kezelésében [Hungarian consensus recommendation on the role of vitamin D in disease prevention and treatment]. Orv Hetil. 2022 Apr 10;163(15):575-584. Hungarian. doi: 10.1556/650.2022.32463. PMID: 35398814.

- Abboud M. Vitamin D Supplementation and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients. 2022 Mar 3;14(5):1076. doi: 10.3390/nu14051076. PMID: 35268051; PMCID: PMC8912284.

- Erdélyi A, Pálfi E, Tűű L, Nas K, Szűcs Z, Török M, Jakab A, Várbíró S. The Importance of Nutrition in Menopause and Perimenopause-A Review. Nutrients. 2023 Dec 21;16(1):27. doi: 10.3390/nu16010027. PMID: 38201856; PMCID: PMC10780928.

- Chen LR, Chen KH. Utilization of Isoflavones in Soybeans for Women with Menopausal Syndrome: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar 22;22(6):3212. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063212. PMID: 33809928; PMCID: PMC8004126.

- Cui Y, Niu K, Huang C, Momma H, Guan L, Kobayashi Y, Guo H, Chujo M, Otomo A, Nagatomi R. Relationship between daily isoflavone intake and sleep in Japanese adults: a cross-sectional study. Nutr J. 2015 Dec 29;14:127. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0117-x. PMID: 26715160; PMCID: PMC4696198.

- Hachul H, Brandão LC, D’Almeida V, Bittencourt LR, Baracat EC, Tufik S. Isoflavones decrease insomnia in postmenopause. Menopause. 2011 Feb;18(2):178-84. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ecf9b9. PMID: 20729765.

- Dasdelen MF, Er S, Kaplan B, Celik S, Beker MC, Orhan C, Tuzcu M, Sahin N, Mamedova H, Sylla S, Komorowski J, Ojalvo SP, Sahin K, Kilic E. A Novel Theanine Complex, Mg-L-Theanine Improves Sleep Quality viaRegulating Brain Electrochemical Activity. Front Nutr. 2022 Apr 5;9:874254. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.874254. PMID: 35449538; PMCID: PMC9017334.

- Zhang Y, Chen C, Lu L, Knutson KL, Carnethon MR, Fly AD, Luo J, Haas DM, Shikany JM, Kahe K. Association of magnesium intake with sleep duration and sleep quality: findings from the CARDIA study. Sleep. 2022 Apr 11;45(4):zsab276. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsab276. PMID: 34883514; PMCID: PMC8996025.

- Razak MA, Begum PS, Viswanath B, Rajagopal S. Multifarious Beneficial Effect of Nonessential Amino Acid, Glycine: A Review. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1716701. doi: 10.1155/2017/1716701. Epub 2017 Mar 1. Erratum in: Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022 Feb 23;2022:9857645. PMID: 28337245; PMCID: PMC5350494.

- Lialy HE, Mohamed MA, AbdAllatif LA, Khalid M, Elhelbawy A. Effects of different physiotherapy modalities on insomnia and depression in perimenopausal, menopausal, and post-menopausal women: a systematic review. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Jul 8;23(1):363. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02515-9. Erratum in: BMC Womens Health. 2023 Aug 9;23(1):419. PMID: 37422660; PMCID: PMC10329343.

- Chiu HY, Hsieh YJ, Tsai PS. Acupuncture to Reduce Sleep Disturbances in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Mar;127(3):507-515. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001268. PMID: 26855097.

- Ugurlu M, Şahin MV, Oktem OH. The effect of music on menopausal symptoms, sleep quality,and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2024 Jan 22;70(2):e20230829. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.20230829. PMID: 38265351; PMCID: PMC10807052.

- Zhao M, Sun M, Zhao R, Chen P, Li S. Effects of exercise on sleep in perimenopausal women: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Explore (NY). 2023 Sep-Oct;19(5):636-645. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2023.02.001. Epub 2023 Feb 8. PMID: 36781319.

- Hulteen RM, Marlatt KL, Allerton TD, Lovre D. Detrimental Changes in Health during Menopause: The Role of Physical Activity. Int J Sports Med. 2023 Jun;44(6):389-396. doi: 10.1055/a-2003-9406. Epub 2023 Feb 17. PMID: 36807278; PMCID: PMC10467628.

- Jeon GH. Insomnia in Postmenopausal Women: How to Approach and Treat It? J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 12;13(2):428. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020428. PMID: 38256562; PMCID: PMC10816958.

- Kim JH, Yu HJ. The Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Depression and Sleep Problems for Climacteric Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 11;13(2):412. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020412. PMID: 38256545; PMCID: PMC10816049.

All of our blogs are written by our team of expert Nutritional Therapists. If you have questions regarding the topics that have been raised, or any other health matters, please do contact them using the details below:

nutrition@cytoplan.co.uk

01684 310099

Find out what makes Cytoplan different

Last updated on 10th April 2024 by cytoffice