Who isn’t exposed to some kind of stress or another, either continuously or just “part time”?

Jobs, finances, relationships, even pets. I love my two Labrador boys to pieces. They do give me a huge amount of pleasure when they behave, but they can also stress me out, for example, when they decide to start barking at the postman in the middle of a work phone call.

Another type of stress I see a lot of is anxiety about one’s own health. Being stressed about a condition you’re suffering from and anxious about getting better can be all consuming and unfortunately a growing number of people I see in clinic have fallen into that vicious circle.

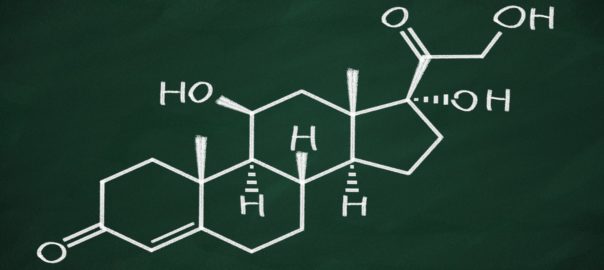

Whatever your stressor, whether it’s dogs, illness or anything else, prolonged psychological stress tends to be accompanied by elevations in blood cortisol known as, “the stress hormone”. This leads to a potential fight-or-flight response we are designed to experience as a short-lived reaction to allow us to either fight or flee (literally) becoming chronic. The results: we’re on edge permanently, sometimes without even knowing why.

If you’ve reached that kind of psychological state where everything is a chore and you’re easily irritated, fatigued or even “not bothered”, it is very likely that cortisol has started to “rewire your brain” in a maladaptive way.

What does this mean and how does it happen.

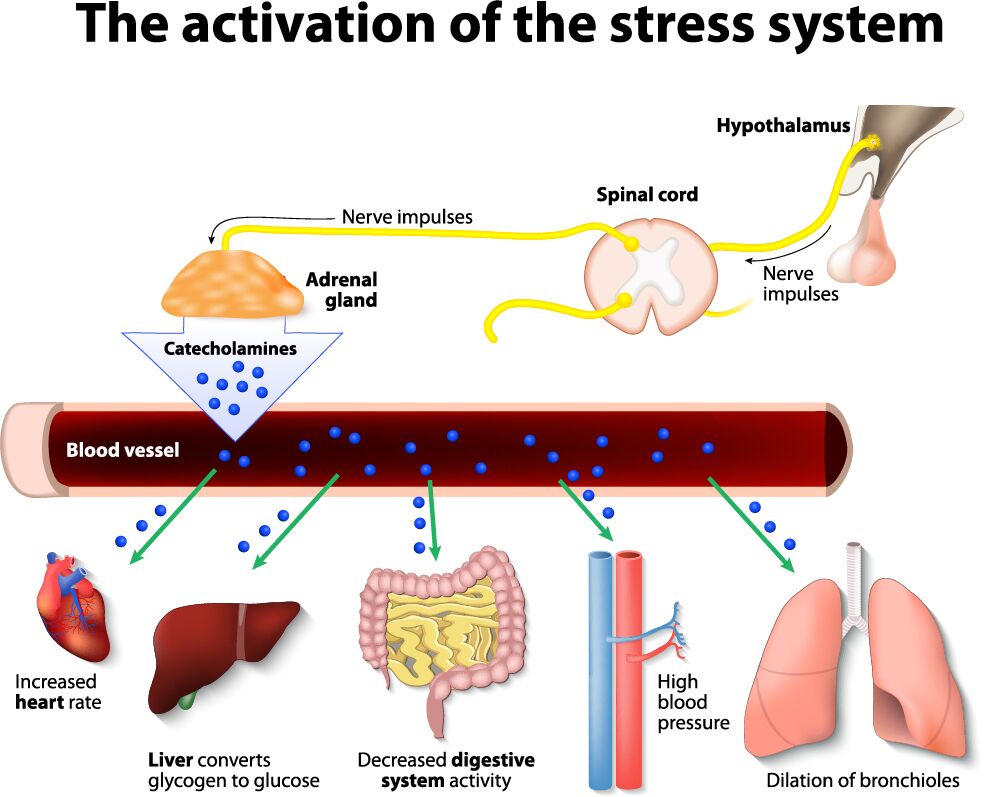

In fact, why does it even happen? Well, cortisol has a number of jobs. It is secreted by the adrenal glands as a messenger to tell muscle and liver tissue to release sugar (stored in these tissues as glycogen) into the bloodstream. That sugar (or glucose) can then be transformed into energy fairly quickly by mitochondria (the tiny power plants inside every single cell of your body) supporting your ability to fight or to flee, whichever of these two actions you might choose to engage in. Only that a lot of the time you have nothing / no one to fight or flee from because whatever is triggering your anxiety is entirely in your head. This doesn’t mean you are imagining things. It’s a loophole in how we are wired to react to stress that evolution hasn’t taken into account. For example, we’ve not evolved (yet) to overcome the fear of missing out (FOMO). My iPhone keeps pinging. It’s Twitter, Instagram, email, phone calls, meetings… If it wasn’t for good old cortisol (and his hormonal brigade adrenaline, and noradrenaline) I couldn’t react to all of that. So I don’t want you to think of cortisol as the bad guy in the movie. It’s just learning how to tame it that’s the important thing, so it doesn’t run wild, running you down with him!

Cortisol is released also as a natural anti-inflammatory substance whenever there’s inflammation to be dampened down, which is partly why inhibiting your ability to react to stress by means of cortisol reduction may not be the obvious answer you may already be thinking of. In fact, cortisol has many other roles, and is involved in the stabilisation of blood pressure and the dilation of the bronchioles in the lungs. It is also one of the molecules that sets the pace of the heartbeat and the activity of the digestive system. If you’re stuck in a fight-or-flight kind of situation, it is most likely that you’ve felt your heartbeat pound harder than normal, or even get palpitations at certain times? Equally your bowel may not move as quickly or efficiently as you’d like it to. These reactions are most likely related to the activation of your “stress system” with cortisol driving these type of symptoms.

Stress and resilience

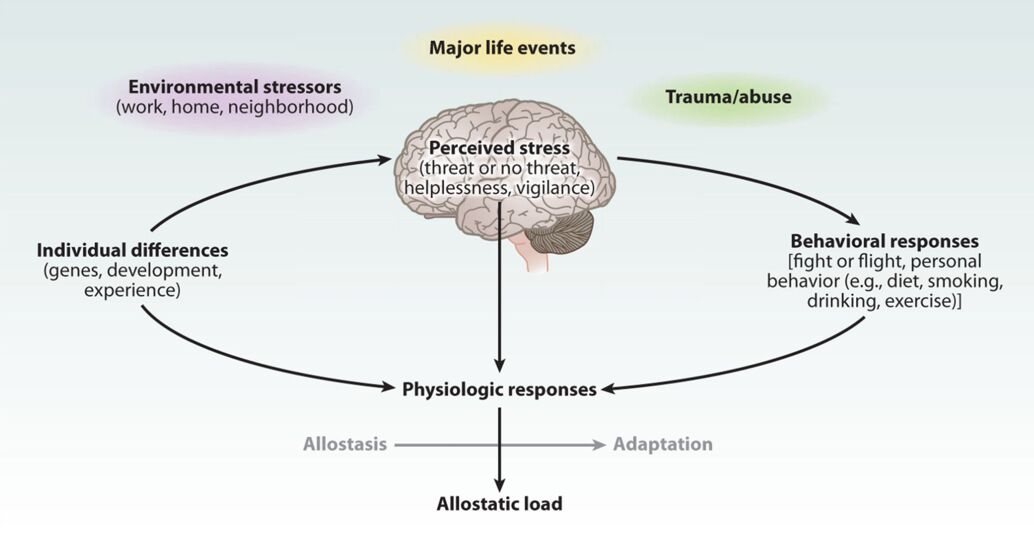

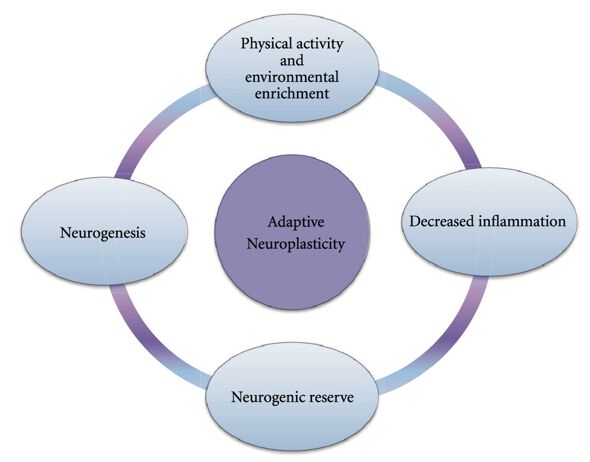

Stressful experiences are not always “bad” for the brain. In fact, in the short term, being exposed to a stressor can lead to growth, adaptation, and new learning. The reason this happens is because the brain is designed as an allostatic system, i.e. a system that is able to find balance (normally referred to by the technical term “homeostasis”) in a dynamic environment. This allostatic or dynamic balance enables you to not only cope with stressful experiences but to adapt to them, regulating your stress levels accordingly, and learning how to manage them. In doing that, new connections are created between neurons that imprint this pattern in the brain so that you know how to deal with the situation in the future. This rewiring is referred to as neuroplasticity and neuroscientists refer to a situation where a stressful situation leads to learning and growth as “adaptive neuroplasticity”. The perfect example is preparing for an exam that you must pass to get a place in university, a promotion or the “Life in the UK” test that’s necessary to get British nationality, like I had to do recently when I decided to apply to become a dual British / Spanish citizen after living here for 23 years. You’re under pressure because you really want to get that job, or that place on that course, or to increase your exotic rating by holding two passports. Cortisol is likely to be high, mobilising all resources necessary to keep you alert. Your pulse will be fast, you’ll be full of beans, you may even feel you need to go to the toilet more frequently as being in that acute fight-or-flight situation, your brain sends signals to your gut that it needs to be empty in case you need to escape from this perceived stressor. The fact is that your brain doesn’t differentiate between the exam and a lion. The stress of the exam is in your head and a hypothetical lion would be real, but really your brain “sees them” as the same thing and responds to them in exactly the same way. Your bronchioles expand so you can get more oxygen into your muscle in case you need to fight or flee the danger. You sit the exam and as the bell tells you it’s time to put your pen down, both your body and your brain crash. Mission accomplished. All those resources that had been mobilised to allow you to achieve your goal are now terminated, and the connections between neurons that were created to enable that extra learning bandwidth become semi-permanent fixtures of your “new” brain.

However, when the activity of allostatic systems is sluggish, ineffective, prolonged, or not terminated promptly, allostatic systems can impair mental and physical health through their maladaptive effects on brain plasticity and metabolic, immune, and cardiovascular pathophysiology (allostatic load).

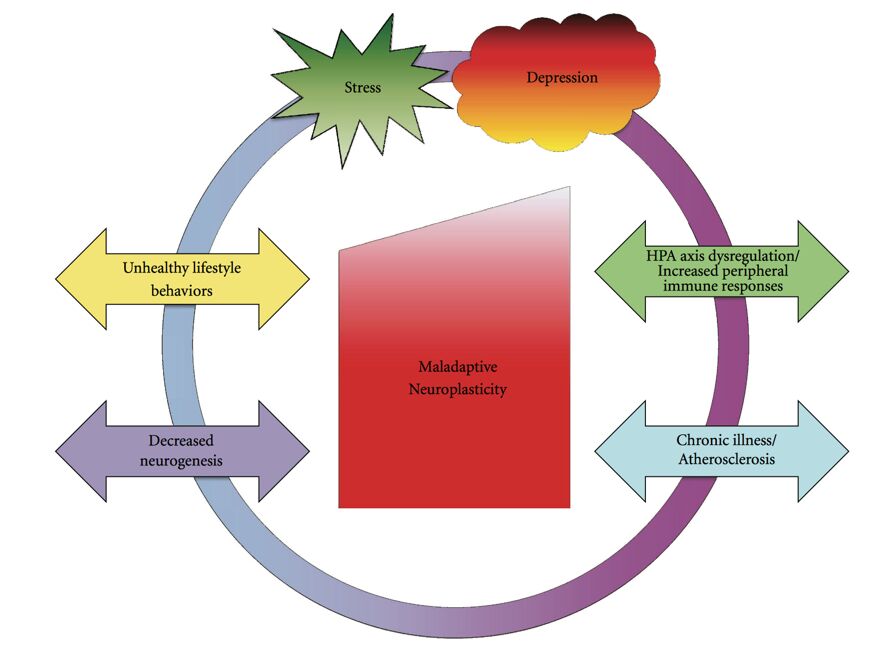

Maladaptive response to stress: When rewiring goes wrong

If your stressor doesn’t go away as in the example of the exam above, and becomes chronic, e.g. worrying about job security, financials, your own health or that of a family member you’re caring for, etc. the effects of stress become problematic for health in the long term, particularly when they’re uncontrollable, unpredictable, and difficult to cope with because of a lack of supportive personal, social, and environmental resources.

In fact, neuroscientists have found that if you’re having to deal with stressful experiences every day the risk of your resilience against physical and mental illness diminishing or even “breaking” is much higher than if you were dealing only with acute stressors. So a little stress is good, but a lot of it is not. In the adult, as well as in the developing brain structural as well as neurochemical changes take place as a consequence of all experiences, including those that are stressful. Modern neuroimaging techniques show that loss of resilience is a key feature of disorders of stress adaptation such as anxiety and depression. Both of these conditions are characterised by maladaptive neuroplasticity, a situation where the connections between neurons I referred to before having established a negative pattern in the brain that has become the default.

What can you do to restore the “adaptive” state?

The brain is the central organ of stress and adaptation. It regulates and responds to a number of factors that contribute to this ongoing balance or allostasis. When the stress system is dysregulated and overused more wear-and-tear of the brain itself leads to subsequent loss of balance in other body systems due to increased allostatic load. Imagine yourself as a boat carrying a heavy load across from the UK to Ireland. Suddenly a helicopter drops another couple of crates for you to carry, making you heavier than you had anticipated and triggering some damage on your hull that lets water in as you start to sink. You get rid of some of the load you need the least by throwing it in the sea, and that makes matters slightly better, before another helicopter drops another couple of crates. Interventions that help you manage your allostatic load include improving your diet. With the right nutrients you’ll not only lighten your load, but also fix your hull so water no longer makes you more prone to sink. Some key nutrients are poly and monounsaturated fats from fish and olive oil, respectively, as well as methyl factor vitamins like folate, B12 and B6, and plant phenols (antioxidants in “old school” science) that help the brain directly and also indirectly via gut-brain communication. Additionally, regular physical activity and having access to a social support and integration, e.g. close contact with friends and family, all help you manage that load so you can continue to sail without having to worry constantly about the excess load and the damage it can cause. A sustainable period of balance promotes adaptive or positive plasticity that can be long-lasting.

Some of the areas of the brain that show both adaptive and maladaptive forms of plasticity, i.e. that are affected by allostatic load, and are implicated in stress-related vulnerability to chronic health conditions include regions of the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala.

Miguel is a doctoral researcher in cognitive ageing who’s experienced the research process from the laboratory bench – having completed a lab-based Masters in Clinical Neuroscience focusing on brain ageing – to the delivery of science findings in the consultation room, delivering quality individualised nutrition care to his clients from 2009. Miguel’s background includes 15+ years in senior training roles in life sciences and medical publishing, and he has trained scientists and researchers around the world.

Miguel is a doctoral researcher in cognitive ageing who’s experienced the research process from the laboratory bench – having completed a lab-based Masters in Clinical Neuroscience focusing on brain ageing – to the delivery of science findings in the consultation room, delivering quality individualised nutrition care to his clients from 2009. Miguel’s background includes 15+ years in senior training roles in life sciences and medical publishing, and he has trained scientists and researchers around the world.

With many thanks to Miguel for this blog; if you have any questions regarding the health topics that have been raised please don’t hesitate to get in touch with me (Clare) via phone; 01684 310099 or e-mail (clare@cytoplan.co.uk).

Last updated on 15th January 2020 by cytoffice

Much shorter paragraphs are needed in order not to scare off those of us who don’t have a scientific background. Break it up. Make it easy on the eye and less of a chore to read.

Dear Jean,

Thank you for your comment. We will happily bear your advice in mind for future blog posts to aid readability.

All the best,

The Cytoplan Editorial Team

I would agree that breaking up the paragraphs may make it easier for lay-people like me to absorb some of this information, but nonetheless I welcome the fact that it is science-based and not dumbed-down. I know a little of the subject already but found this article very helpful in pulling that information together and furthering my understanding of both neuroplasticity and the mind/body connection. Many thanks for publishing it.

It did seem daunting to begin with I agree! But if u have a genuine interest u will read.

I thought it was an amazing article!

Similar to what I learned doing the lightning process.

I have no science background just common sense and I found it really interesting

I was thinking the very same thing on paragraphs or an edited version to break up the information and help to absorb it better.

I think that our brains and our eyes appreciate spacing!

The article is so interesting and goes into amazing detail .

Thank you:)

Very easy to understand science behind what makes common sense. Will post this on facebook for my stressed out friends.

I would be very interested to hear more about the stress of bereavement and it’s effects, particularly where the loss is a spouse and totally life-changing. The chances of suffering major illness or death are much increased after an event like this and many people never get “over” or recover to the point where they can live again. In some ways it is impossible to get over it but too sad for words to live in the acute pain of loss for years and years. More study and advice is so needed in this area.

Flower Essences like Bach Flower and Australian Bush Flower Essences have

their place in helping this very difficult process from a therapeutic point of view also Homeopathic Ignatia has a good track record❣️

Please make it easy to print your articles on an A4 sheet so I can give to clients or post to elderly relatives without computers!

Very interesting, my interest is trying to generate new neuroplasticity in my brain to try and heal my MS. Obviously the gut plays a major part so I read your blogs trying to educate myself.

Hi Diana

I hope u don’t mind me messaging you.

U might want to look into the Lightning process

It really helped me. It helps with all sorts of conditions

I had an auto immune disease along with a billion other problems! And it transformed my life.

The course covered fight or flight and then tools on how to get out of the stress response and stay out of it.

Good luck

I read your reply to Diana.

I have MND ( motor neurone disease) I live alone with no family and anxiety is causing me to wake in the early hours and be unable to sleep again. I will lookup the Lightening process,

Thank you

I find these articles really interesting and I have nutritional background so they are not difficult. Breaking them up with more headers and a summary would be good too – maybe a non-nutritionist paragraph that we can give to clients. It would be good to have a print option otherwise it comes out over several pages.

I agree, I looked for a print option & am disappointed there isn’t one.

What a great article! Although I am a lay person Miguel’s way of explaining the complexity of the mind and body and stress related disorders made everything seem so easy to understand. I have to disagree about an earlier reply which asked for shorter paragraphs and to make it simpler. I can find and simple anywhere on line about anything. What I can’t get is an article with this depth made easy for me. Well I can because it’s here. Please don’t dumb down. If I can get my gut and stress levels sorted and be the person I was fifteen years ago I will pretend I am a Practitioner and come to the event.

Approximately a year ago I had a telephone consultation regards balancing my hormones & was shocked to discover that I still hadn’t recovered from 5-6yrs of stress due to financial reasons.

Having taken early pensions & easing the financial burden I thought I was better- but I wasn’t, the stress had indeed rewired my brain. I did do some research into stress but at the time, found little help- I think it’s because the subject goes across disciplines so, Miguel’s article is a welcome one.

Despite low finances I did take supplements and had a good diet so I remain a little skeptical regards which “lifestyle interventions” could help someone suffering from chronic stress.

I found this very interesting and informative. I wonder if you plan to run the day event anywhere else for example near Cheltenham?

Excellent article. Would have loved to have been able to print it out minimally in order to show to friend who has PTSD. She was put on beta blockers by GP! Typical pill pushing for symptoms with no effort to look at cause and remediate accordingly.

Fantastic article beautifully written and well explained, could do with some references though for further research.

The most well-written article I’ve read on stress (and I have read a lot having severe gut issues and cancer). Great that it is not dumbed down: it means that we learn about the subject correctly! But it was explained simply and clearly enough that I understood it. I too am disappointed that I can’t save or print.

Also slightly frustrating is that I did not receive a link to this article until over a week after the talk! I am not a practitioner but I know one who would have loved to attend!